Vascularization Strategies

If you’re looking to culture large tissue constructs over long periods of time, you will need to consider how your cells will be supplied with nutrients and oxygen and how their waste will be removed whilst they mature.

- Have you considered how the network to supply this will look?

- How will you insert/extract the culture, and how will it be manufactured/maintained?

- Do you need multiple distinct channel networks to supply growth factors, or other optical/mechanical stimulation?

Every part of this must be compatible: a few manufacturing strategies are presented here with appropriate vascular designs.

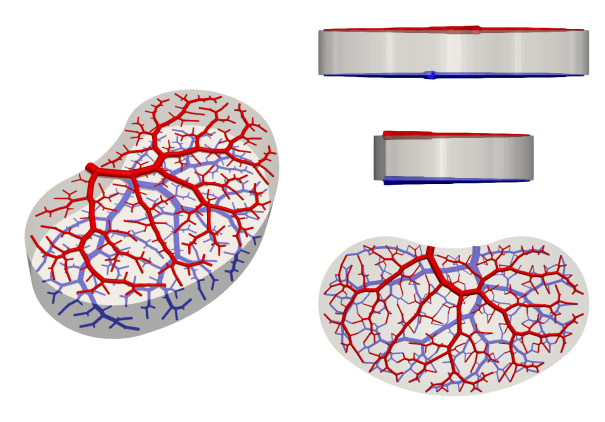

Full 3D

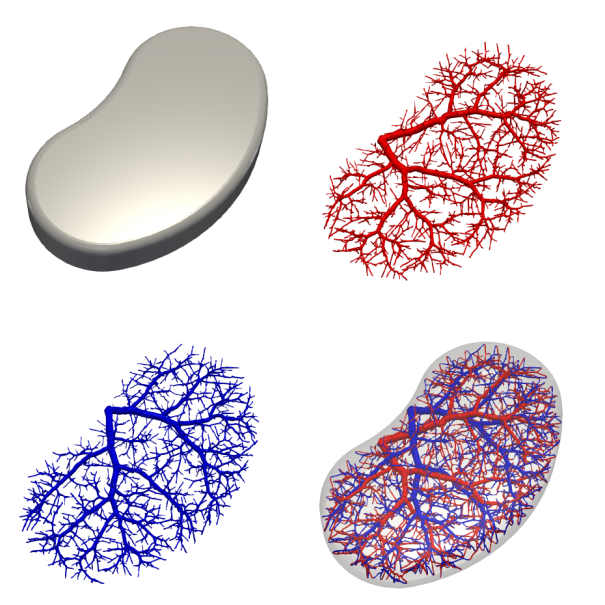

The first thing to do is design the outer geometry and conencting points of our domain: let’s start with a nice kidney-shaped blob of tissue. Using our connection and bounding geometry, we can design a mould to contain the tissue as it matures — you may need to add additional ports for casting, if you’re using a sacrificial approach. The next thing to do is design the vascular network to supply our tissue: there are a number of relevant parameters:

- Cell-channel spacing (equivalently, channel-channel spacing): depends on minimum manufacturable feature size and initial cellular density.

- Inlet/outlet radius: depends on minimum feature size and overall construct size, flow rate and intended pressure drop. Copying biological values tends to work quite well.

- Inlet/outlet location and direction: how are you going to connect your construct to the outside world?

My software can create these designs with little effort, for any number of distinct interpenetrating networks.

The next thing to do is consider your manufacturing approach. Most approaches will aim to create perfusable channels in a hydrogel construct:

- Sacrificial methods: create a sacrificial template, cast hydrogel around it and then remove the template. A variety of methods for creating the templates exist, including electrospinning, laser sintering, extrusion/inkjet printing and photopolymerization. The advantage of this approach is that the casting step is rapid, allowing the gel to be laden with cells and cast around an arbitrarily detailed template.

- Direct bioprinting: either extrusion or inkjet printing of cellular inks, allowing you to control the spatial concentration of the tissue. This approach has fundamental trade-offs between feature size, printing rate and overall construct size, given that the construct must be perfused before the first cells die. Create the channels either as a void or sacrificial ink to be cleared later.

- Subtractive methods: starting from a hydrogel block, remove material to create the channels. For example, a laser can be used to ablate material with very high resolution, although the manufacture time can be very long and any cells in the gel will be damaged by the laser.

After this, we have the option to seed cells in the channels (e.g. endothelial cells) as well as directly injecting cells/organoids in the interstitial space, now that the gel is perfused and can support denser cultures.

From there, we must fine-tune the concentration of solutes and flow rate profiles over time in each of the channel networks to encourage tissue growth (e.g. establishing cytokine gradients across an interpenetrating exchanger pair to encourage invasion across the tissue), ramping up flow rate as the metabolic requirement of the tissue increases. The competing cost of work done pumping fluid through the networks and solute consumption can impact the design of the optimal network, so a suite of networks with various cost ratios may need to be tested to identify the most efficient structure for manufacture.

2+1D

For bespoke tissue constructs, the high cost of manufacturing in 3D is likely to be worth it. But for mass-produced, lower value constructs, we may find that the desired construct is small enough to justify perfusion via embedded columns rather than a full 3D design. This approach resembles a more traditional microfluidic approach, with a 2D distribution network recessed into the upper and lower surfaces of the mould, and has the advantage of being simple to disassemble, sterilize and reuse. Compared to free-fluid flow over the surfaces, channel networks distribute the flow uniformly with a single connection to inlet/outlet tubing, as well as permitting more complex interpenetrating structures depending on the acceptable complexity (i.e., number of layers you are willing to bond together).